Online collections

monedastodas.com

All collections » Tokens » Revolution Tokens

Propaganda coins of Thomas Spence and his contemporaries

At certain historical points in Britain, the official issue of small coin was quite scarce, so unofficial coins were put into circulation. This was due to the low denomination of coins, which, at the same time, required significant production costs and which were not necessary for the state's own needs. However, for the common man, the lack of small denominations was a big problem. For example, if he received 15 silver shillings a week, and wanted to buy bread for a penny and a half, he had coins of too large a denomination in his hands and the shopkeeper could not return change. There was a shortage of small change during the English Civil War, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. During these periods, a large number of unofficial coins of small denominations were issued,

Copper

token by Thomas Evin, Cambridge, 1668

Copper

token by Thomas Evin, Cambridge, 166818th century tokens

Thanks to the development of the copper industry in the eighteenth century, the metal became more accessible and cheaper, and the new minting techniques of Matthew Bolton's well-known Soho Mint, made it possible to mint more coins with less labor. At the same time, there were a large number of talented engravers to produce stamps. All this contributed to the wide distribution of various stamps for the production of tokens, many of which are real works of art, which causes a large number of token collectors around the world. And although the problems with the issuance of small coin after 1792 for the most part ceased, a large number of tokens continued to be issued for such enthusiasts in the form of commercial coins.

Halfpenny

issued by Dodd, London, 1785

Halfpenny

issued by Dodd, London, 1785Since such tokens were supposed to guarantee the possibility of exchange for official money, at least in theory, the names of their issuers were applied to them. Some of them, such as Mr. Dodd above, were unable to resist the temptation not to depict themselves in royal style, in the manner of real British coins. Others, seeing the possibilities of changing hands as means of payment, advertised their goods and manufactures in more sophisticated ways:

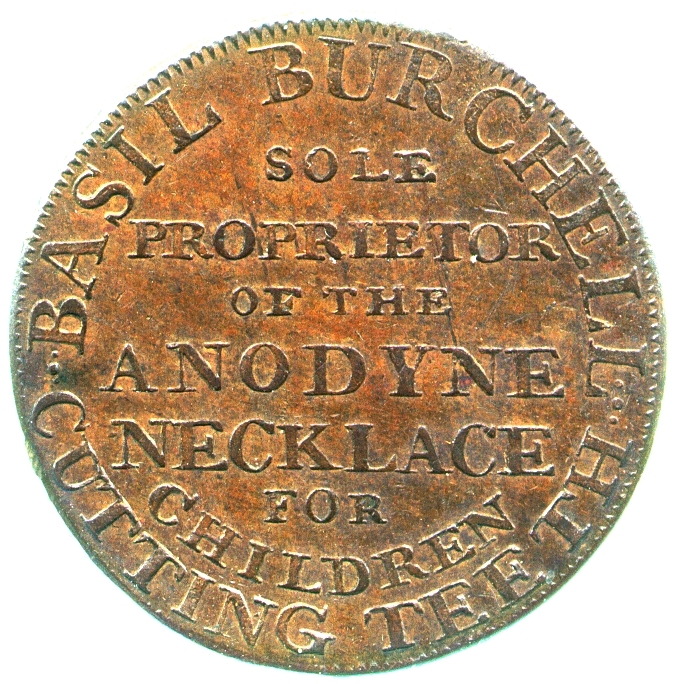

Reverse

side of a halfpenny by Basil Burchell, London pharmacist, late 18th century

Reverse

side of a halfpenny by Basil Burchell, London pharmacist, late 18th century  Reverse

side of a halfpenny by Kelly Saddlery, London, late 18th century

Reverse

side of a halfpenny by Kelly Saddlery, London, late 18th century  Reverse

side of a halfpenny issued by Niblock of Bristol, 1795

Reverse

side of a halfpenny issued by Niblock of Bristol, 1795Showmen and spectators

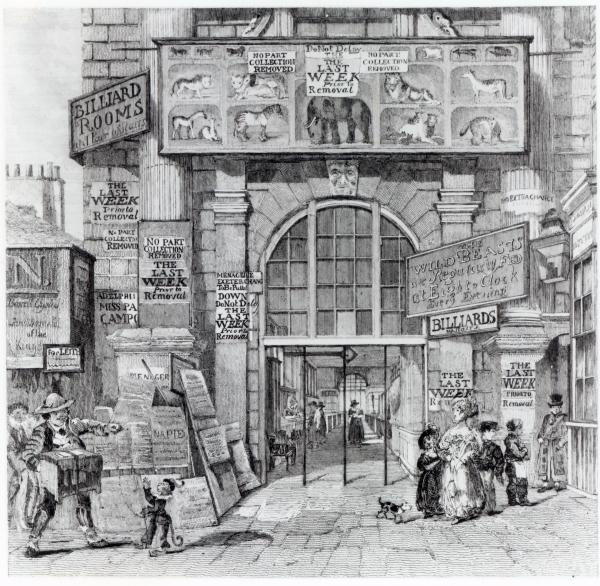

The followers of bright and eloquent messages that can be passed in the pockets of people in the form of symbolic advertising were the owners of theaters and circuses. The largest series was produced by Gilbert Pidcock, owner of the Pidcock menagerie on the Strand.

The

obverse side of the halfpenny advertises Pidcock's menagerie, engraver C. James,

issued by William Latvich for Gilbert Pidcock, 1795.

The

obverse side of the halfpenny advertises Pidcock's menagerie, engraver C. James,

issued by William Latvich for Gilbert Pidcock, 1795. Pidcock was not the only one to advertise such entertainment.

Halfpenny

front side advertising the Luceum Theater on the Strand, engraved by Roger

Dixon, produced by William Latvich

Halfpenny

front side advertising the Luceum Theater on the Strand, engraved by Roger

Dixon, produced by William Latvich  Halfpenny

reverse side, engraved by Benjamin Jacobs,

Halfpenny

reverse side, engraved by Benjamin Jacobs,

Tokens for Collectors

Particularly in London, where there was a

large market due to population density, tokens themselves served as commodities,

representing objects of artistic or historical interest to a large number of

collectors of the time, which appeared with the issuance of this unofficial

money. Often this was explicitly stated.

The

reverse side of a halfpenny issued by Flitwick for John Skidmore in 1797, the

inscription reads: "Dedicated to collectors of Medals and Coins"

The

reverse side of a halfpenny issued by Flitwick for John Skidmore in 1797, the

inscription reads: "Dedicated to collectors of Medals and Coins"The most famous producers of tokens for collectors are Peter Kempson of Kempson, Kindon of Birmingham and John Skidmore of London. Kempson and Skidmore issued many tokens depicting famous old architecture, especially London, and many of the buildings remain recognizable even today.

Halfpenny

obverse depicting the Mansion House in London, by Thomas Wyon, issued for Peter

Kempson, late 18th century Halfpenny obverse

Halfpenny

obverse depicting the Mansion House in London, by Thomas Wyon, issued for Peter

Kempson, late 18th century Halfpenny obverse  from

the John Skidmore Architecture Series, engraver Benjamin Jacobs, late 18th

century

from

the John Skidmore Architecture Series, engraver Benjamin Jacobs, late 18th

century  Halfpenny

verso depicting St Paul's Church, Covent Garden after a fire in 1795, engraver

James for John Skidmore

Halfpenny

verso depicting St Paul's Church, Covent Garden after a fire in 1795, engraver

James for John SkidmoreHowever, commercial and artistic images are not the only things that could be transferred using tokens.

Political tokens

Other issuers addressed the public with pressing military issues, patriotic slogans, and the need to be loyal to the king. There were also issues depicting the beleaguered French royal family of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

The

reverse side of a halfpenny commemorating the Prince and Princess of Wales. Engraver

Thomas Vyon for Peter Kempson, late 18th century

The

reverse side of a halfpenny commemorating the Prince and Princess of Wales. Engraver

Thomas Vyon for Peter Kempson, late 18th century  Halfpenny

verso with legend: "Fear God and honor the King", issued by William Williamson,

London, 1795

Halfpenny

verso with legend: "Fear God and honor the King", issued by William Williamson,

London, 1795  Halfpenny

verso depicting King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette, issued by Peter

Skidmore , 1795,

Halfpenny

verso depicting King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette, issued by Peter

Skidmore , 1795,  halfpenny

verso, maker unknown

halfpenny

verso, maker unknown

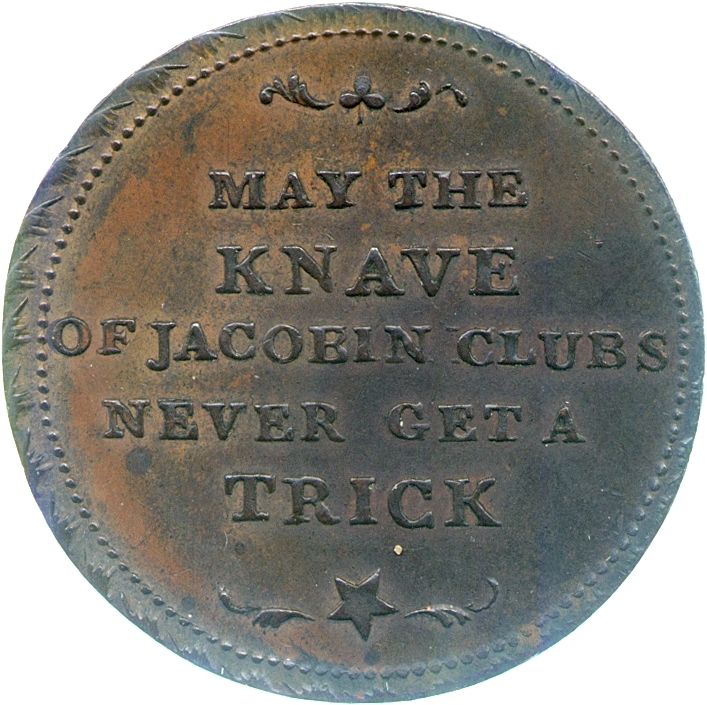

Revolution and Reform on English Tokens

England avoided revolution in the image

of America and France, but the common language and shipping lanes between them

and their new governments meant that the thinking and arguments of the

revolutionaries abroad were similar in England itself. Particularly

prominent is a text calling, if not for revolution, at least as a reform called

The Rights of Man, published by Thomas Paine in 1791, which defended the rights

of citizens to oppose unjust authority, and also called for to the writing of

the Constitution and a progressive income tax aimed at preventing the emergence

of hereditary aristocrats. Payne's publications brought him to

trial for sedition, but he managed to escape execution by fleeing to France.

Portrait

of Thomas Paine

Portrait

of Thomas PaineSedition trials in late eighteenth century England were not uncommon, and the country was not a safe place to oppose the incumbent government. However, those who still expressed their disagreement did so not only in printed works, but also in metal. The possibilities for the free production of tokens for collectors or commercial use were practically beyond the control of the state, and were obvious to those who wished to spread propaganda. against the state, and although engravers and manufacturers were happy to accept orders from such individuals, if necessary, they could acquire the necessary mechanisms for the production of tokens without outside help. Gatherings of dissidents who were too visible, or who were willing to celebrate one of the few victories against the status quo,

Halfpenny

issued by the London Correspondent Society depicting the fable of the bunch of

brushwood (The Bundle of Sticks), 1795.

Halfpenny

issued by the London Correspondent Society depicting the fable of the bunch of

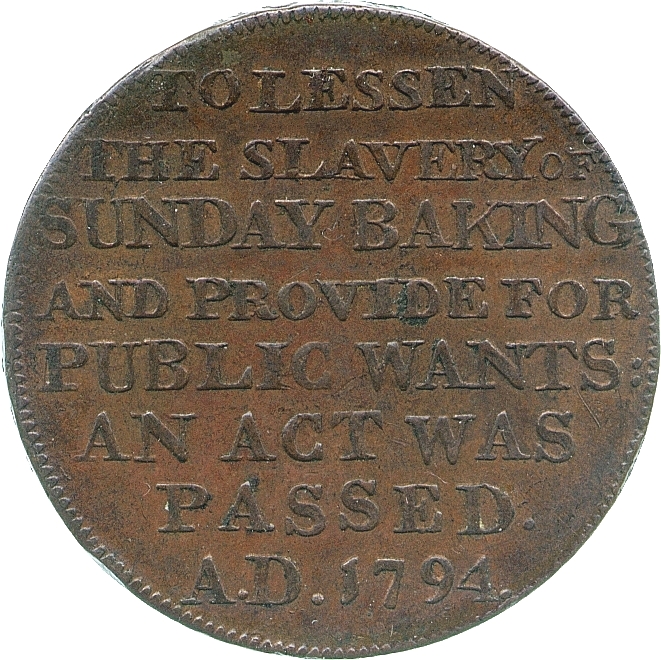

brushwood (The Bundle of Sticks), 1795.  Reverse

side of the halfpenny issued by the baker Dennis of London, 1794.

Reverse

side of the halfpenny issued by the baker Dennis of London, 1794.The danger and isolation of dissenting camaraderie led to dark humor that made these tokens witty enough, but often difficult to understand. The example below mimics commercial issues that guarantee the exchange of tokens for official silver coins at the address of the manufacturer (Payable at the ...), but the address on the reverse side shows Newgate Prison, in which four men were previously imprisoned for sedition.

Obverse

and verso of a halfpenny issued by Peter Kempson listing prisoners Henry

Symonds, William Winterbotham, James Ridgway and David Holt, engraver Thomas

Wyon, 1795

Obverse

and verso of a halfpenny issued by Peter Kempson listing prisoners Henry

Symonds, William Winterbotham, James Ridgway and David Holt, engraver Thomas

Wyon, 1795The implication of this token is based on the assumption that everyone who happens to receive the token will be able to find out the names of the prisoners. This in itself shows that the deeds of the revolutionaries were the subject of a public account in London. Two men named Henry Symonds and James Ridgway were jailed for publishing Payne's book. The engraving below, created from the life of Richard Newton during his stay at Newgate, shows that if there were enough free space on the token, the names of many other radicals could be added. The conditions of detention may seem comfortable, but two of the men depicted in the engraving died and two more fell ill with typhus within a year. Symonds and Ridgway are depicted in the engraving seated on chairs in the right foreground.

Soulagement

en Prison or Comfort in Prison, an engraving created by Richard Newton and

published on August 20, 1973.

Soulagement

en Prison or Comfort in Prison, an engraving created by Richard Newton and

published on August 20, 1973.Of course, not everyone who participated in the publication of revolutionary literature went to prison, there were also enterprising like-minded lawyers to defend the radicals. At the request of two such lawyers, Thomas Erskine and Vicar Gibbs, the token shown below was produced to advertise their own services. It depicts two lawyers, each holding a banner: Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights. For the most part, this token is intended to emphasize the skill of defending lawyers, listing on the reverse side the names of those who were successfully protected from imprisonment.

Obverse

and verso of a halfpenny for lawyers

Obverse

and verso of a halfpenny for lawyersHowever, there were token producers who went even further…

Thomas Spence

Bust

of Thomas Spence, featured on one of his halfpennies, commemorating his

imprisonment for sedition in 1794

Bust

of Thomas Spence, featured on one of his halfpennies, commemorating his

imprisonment for sedition in 1794The most active producer of tokens for the purpose of revolutionary propaganda was Thomas Spence. His radicalism was not like that of all the other radicals. Born in Newcastle in 1750, by the age of twenty-five he was already politically active and developed a plan for land reform, which provided for the communalization of all landed property, the abolition of landowners and rents (advocated the abolition of private ownership of land and the transfer of it to church parishes for free on this basis, Spence considered it possible to create a new social order - a free association of self-governing communities). He published it in 1775 with the title Property in Land: Every One's Right but, losing nothing to political fashion, and republished in 1793 under the title The Real Rights of Man. Despite the name, he actively supported the work of Paine, which he sold in his London shop in 1794 (for which he was imprisoned for a while), and did not lose the opportunity to associate himself with the 'other Thomas', but it is unlikely that Paine with his communist ideas agreed to this analogy.

Fragment

from the catalog describing Spence's first token,

Fragment

from the catalog describing Spence's first token,On the obverse of the farthing below, Spence is mentioned as one of the three Thomases, "Defenders of the Rights of Man", the other two being More and Payne. The reverse side advertises Spence's weekly publications called "Pig's Meat", a title referring to Edmund Burke's "the swinish multitude".

The

front and back of a farthing by Thomas Spence, 1796

The

front and back of a farthing by Thomas Spence, 1796

Spence was initially wary of the

propaganda potential of tokens, and his first issue, commemorating the

publication of a plan for land reform in 1775, predated the “token mania” by

several years, making these tokens quite rare. However, after

settling in London, he not only discovered a ready market for tokens, which

later proved to be more effective than selling books, but also began a fruitful

collaboration with the engraver James, whose willingness to embody Spence's

ideas, depicting them in his lively and vibrant rebellious style, which, as a

result, were far ahead of Spence's bombastic prose not only politically, but

also more clearly reflected his feelings of indignation and indignation at the

prevailing situation in the country. The result was a kind of

immortality that Spence could not have even wished for,

“... some of them, due to their deep

meaning, others, due to the craftsmanship, and all due to their great diversity,

will attract attention to themselves many years later.”

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence halfpenny, late 18th century

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence halfpenny, late 18th century  Reverse

side of Thomas Spence halfpenny, 1975

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence halfpenny, 1975In some of his most successful token images above, Spence displays outspoken idealism coupled with heavy irony about the injustice of today. The token with the circle legend “The End of Oppression” depicts revolutionaries around a campfire with burning land charters, the other shows a citizen captured by a recruiter for naval service and the circle legend: “Reflection of British Liberty” (British Liberty Displayed) .

Spence's Utopia

As might be expected from his systematic return to the ideas of the primitive commonwealth, Spence's thoughts on human rights stem from the idea that, under natural conditions, a person could use the land as he pleased, and no one would claim these possessions. In rent and taxes, Spence saw the immoral burden of relics of the past on inalienable freedom, and punctuated these issues with tokens, sometimes overloading the design with his own rhetoric. The token below shows a donkey loaded with two sets of baskets, the bottom pair of baskets is labeled “Rents”, the top one is “Tax's”, and the circular legend reads “I was an ass carrying the first pair”(I was an Ass to Bear the First Pair).

The next token depicts an American Indian with a bow and tomahawk, and the circle legend reads: “If rents I once consent to pay, my liberty is past away.”

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence's halfpenny, late 18th century

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence's halfpenny, late 18th centuryThe images of these two tokens refer to the works published by Spence in 1796 and quote some of their key points. Similar utopian views are clearly shown in the next two tokens. On the farthing below, which depicts Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the circular legend reads "Man over Man Made He not Lord".

Obverse

side of a farthing by Thomas Spence, late 18th century

Obverse

side of a farthing by Thomas Spence, late 18th centuryA halfpenny below shows a shepherd resting against the backdrop of a magnificent scenery of the English countryside, for which James received the highest praise for his elaborately engraved image.

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence's halfpenny, late 18th century

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence's halfpenny, late 18th centuryMany of Spence's tokens were created based on contrasts, such as front and back, as well as images or legends, a device that gave his sharp satirical wit full play. The next token shows the eternal struggle between cats and dogs, where Spence took the side of the cats ... The obverse depicts a dog with its paw raised in request, and the circular legend reads: "Much Gratitude Brings Servitude", while on the reverse with a depicted cat, the opposite legend: “I Among Slaves Enjoy My Freedom” (I Among Slaves Enjoy My Freedom).

Obverse

and reverse of Thomas Spence's halfpenny, 1796

Obverse

and reverse of Thomas Spence's halfpenny, 1796In some cases, Spence and James avoided subtlety by using the power of images and legends. Again, James' craftsmanship brought his wildest imaginations to life, which makes these tokens stand out more than Spence's genuine sentiments.

Pair

of obverse sides of different tokens by Thomas Spence, late 18th century

Pair

of obverse sides of different tokens by Thomas Spence, late 18th centuryThe token on the left depicts an emaciated man sitting in prison, gnawing on a bone and a circular legend: “Before the Revolution” (Before the Revolution), which contrasts with the token on the right, depicting three dancing men and another who dine lavishly at a table under a tree, with a circular legend that reads: "After the Revolution" (After the Revolution). For all his revolutionary fervor, for the most part, Spence was a patriot. He wanted to change England almost completely, but at the same time he was sure that the British were better off and freer than the French. The next pair of tokens clearly illustrates his attitude towards this issue. The clarity with which he sometimes showed which side he took in the war may have saved him from legal proceedings. In this, as in many other things, the difference between Spence and Payne is clearly visible.

Obverse

sides of two halfpennies by Thomas Spence, late 18th century

Obverse

sides of two halfpennies by Thomas Spence, late 18th centuryThe first token depicts a well-fed man having a fine meal with a circular legend: “English Slavery”, and the second depicts a thin man in a hat gnawing bones on a folded blanket in front of a lattice with a circular legend: “French Liberty”. However, Spence's determination to reform, as well as his claims to equality with Payne, sometimes escalated into genuine hatred, countered by opponents' issued tokens ...

Reverse

of copper halfpenny by Thomas Spence, 1795

Reverse

of copper halfpenny by Thomas Spence, 1795  Reverse

of copper halfpenny by Thomas Spence, 1795

Reverse

of copper halfpenny by Thomas Spence, 1795With the help of the tokens above, Spence's hatred of injustice and power "overflowed" the cup to some extent. While the message is not clear enough, the first token at the top of the Liberty Tree, the traditional symbol of liberty, has replaced the Phrygian Cap with the head of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, which Spence describes as “the head of a protector.” human freedoms” (the head of the protector of men's liberties), perhaps he himself understands that this is propaganda of violence, if he made it clear that he was ready to go further than the authorities could allow. In the same way, although this is not confirmed by any legend, the guillotine, ready for work, seems to warn lovers of freedom from the previous token.

Conservative tokens

Of course, the revolutionaries had opponents who opposed them, also resorting to propaganda on tokens, as Spence and his accomplices did. Some issuances of tokens address major issues of political change, such as making strong and decisive statements about the organization of the state, using the power of visualization almost as expressively as Spence and James did.

Halfpenny

obverse, late 18th century, engraver Roger Dickson, maker William Lutwich

Halfpenny

obverse, late 18th century, engraver Roger Dickson, maker William Lutwich  Halfpenny

obverse by William Williams, 1795

Halfpenny

obverse by William Williams, 1795The first token depicts the three powers of England: the King, the Lords, the People, which make up an indestructible triangle, in the center of which the Constitution is depicted. It should be noted, although it looks more conservative than Spence, writing a constitution was a common goal of the reformers. The unknown issuer here says that a constitution is sufficient to unite the three estates, or that all three estates must become one? Perhaps this ambiguity was made intentionally in order to sell the token to as many people as possible, regardless of their opinion. William Williams, the issuer of the second token, was less ambiguous, using the coat of arms of the Prince of Wales as the main element of the composition, but even here the biblical legend is given:

Obverse

and verso of a halfpenny by engraver William Mainwaring, 1794

Obverse

and verso of a halfpenny by engraver William Mainwaring, 1794The next token uses a rather thoughtful composition. On the obverse, the conceptual map of France is taken as the basis, in the center there is HONOR trampled down by foot, an inverted THRONE, GLORY destroyed by cross-hatching and RELIGION smashed to smithereens, blood flows from the word FRANCE in wavy lines, and fire burns in every corner and this whole composition is in surrounded by daggers. The moralizing legend on the reverse side reads: "May Great Britain ever remain the reverse" - the play on words in the center of the image is opposed to the other side of the token. While such allusions may seem overly complex, William Mainwarign struck with the metaphorical richness of his portrayal, which was used in twenty different editions and three different metals (although they were not produced from gold). This popularity can be explained by the horror and fear of the English, based on the news from France, where the Revolution had reached its final and most bloody stages.

Attacks on Spence

Because of his outspokenness, both textual and visual, and no doubt his undeniable self-importance, Spence and his ideas were a particular target for other token producers whose views on the system of power were more conservative. Although Spence and James made the dies for the minting of their tokens, their opponents were able to benefit from it, as the dies remained the property of the makers and could be used by anyone. This gave opponents of Spence's ideas an excellent opportunity to mock him using the design of his own tokens.

Obverse

of a halfpenny issued in the name of James Spence, late 18th century.

Obverse

of a halfpenny issued in the name of James Spence, late 18th century.The token above shows a snide joke about the Spence family's humble origins, a redesigned drawing depicting the begging of a former sailor (who was actually Spence's brother), now with a new legend: “J. Spence, slop seller, Newcastle” (J. Spence Slop-Seller Newcastle). Less innocuous is the token below, which, based on Spence's "Three Thomases" token, where three human rights advocates are mentioned, depicts three people hanging from the gallows, who are satirized by Spence's altered legend: "Noted Advocates of the Rights of Man).

Reverse

of halfpenny engraver Thomas Wyon, 1796

Reverse

of halfpenny engraver Thomas Wyon, 1796An equally nasty mockery of Spence's work is depicted on the farthing below. The obverse depicts a man hanged on the gallows and a circular legend that reads: “End of Pain”, ambiguously alluding to the desire for a similar end for the radical of the same name, the third Thomas (meaning Thomas Paine), since his work, as well as the Plan Spence, under his second populist title, are ridiculed on the back of the farthing, which shows an open book entitled The Wrongs of Man and the date of the execution of King Louis XVI of France.

Front

and back of a farthing, unknown manufacturer, 1793

Front

and back of a farthing, unknown manufacturer, 1793Issues of such tokens are perhaps malicious responses to Spence in pockets and tongues.

Socially conscious currency

Since conservative opinion will allow a little talk about him, the issues that Spence and other protesters drew attention to did not cease to exist. Some of the comments on these issues in the tokens were borrowed from Spence's tactics, in particular, in a combination of images of the front and back sides that contrast with each other in meaning. The token below plays on this technique, expressing an opinion about the sailors who got into an unpleasant life situation and were dismissed after faithful service to the Royal Navy in a way that Spence would have been pleased with. The obverse depicts the sailor hero Tom Tackle brandishing a saber with patriotic fervor and a legend at the bottom that reads "For the King and the Fatherland"; on the reverse side, the former sailor is depicted begging with his hand outstretched, on a wooden prosthesis, leaning on two sticks,

Obverse

and reverse of halfpenny, unknown manufacturer, late 18th century

Obverse

and reverse of halfpenny, unknown manufacturer, late 18th centuryArguably the most famous social token of the entire period, whose imagery was so powerfully used by William Wilbers, is shown below, known in numerous variants and testifying to the injustice of slavery. On the front side, on his knees, a negro asks: “Am I not a man and a brother?” (Am I not a man and a brother?), while on the reverse side, hands joined in a handshake are placed inside the motto: "May slavery and oppression cease throughout the world." This edition was probably produced in Dublin.

Front

and back of a halfpenny issued by the Society

Front

and back of a halfpenny issued by the SocietySpence's last word

To the extent that was possible in the quiet environment of the underground, Spence was undoubtedly very vocal and opinionated, making a living by people's willingness to buy tokens, prints, and pamphlets professing revolutionary ideals. He was not afraid to try to ride the tails of other more famous, successful and respected radicals, and for all these things his opponents tried to refute his claims. On the other hand, he was undoubtedly driven by a sense of justice in a society whose imperfections he clearly felt and could powerfully express using artistic imagery, perhaps even more vividly than in print (although his ability to slogans may be the envy of many modern marketing departments). Most of his life he spent in poverty because of the relentless struggle for his cause,

Consider two more tokens that show that he suspected his role in London's political unrest, but also defended his radical activities as a genuine strategy for ending injustice and oppression.

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence's halfpenny, 1795

Reverse

side of Thomas Spence's halfpenny, 1795The first token depicts a lion representing tyranny pursued by the loud cry of a rooster perching on its back, consistent with Spence and his opponents, though perhaps not with the legend: "Let Tyrants Tremble at the crow of Liberty).

The last token depicts another of James's incredible pastoral scenes, using a humble snail, to which Spence added a defiant legend: "A Snail May Put His Horns Out". Even today, various manifestations of protest can find some sense of camaraderie in this modest display of strength.

Reverse

side of a Thomas Spence halfpenny, late 18th century.

Reverse

side of a Thomas Spence halfpenny, late 18th century.Additional materials

Spence's tokens were cataloged by numismatists Richard Dalton and Samuel Henry Hamer, authors of the most comprehensive token catalog of the 18th century. Information originally part of a larger catalog has recently been revised and reprinted in one volume: R. Dalton & SH Hamer, The Provincial Token-Coinage of the 18th Century Illustrated, rev. Allan Davisson (Cold Spring: Davisson's 1990). Another relevant book is P. & B. R. Withers, The Token Book: 17th 18th & 19th Century Tokens and their Values (Llanfyllin: Galata 2010), but this only illustrates some of the examples. Detailed information on the production and market of tokens can be found in Richard Doty, The Soho Mint and the Industrialization of Money (London: British Numismatic Society 1998), or in two articles from 2003: Peter Mathias, "Official and Unofficial Money in the Eighteenth Century: the evolving uses of money. The Howard Linecar Memorial Lecture 2003" in British Numismatic Magazine Vol. 73 (London: BNS 2003), pp. 69-83, and David Dykes, "Some Reflections on Provincial Coinage, 1787-1797", ibid. pp. 160-74. Nothing significant is said about Spence, but Dykes calls him a "reckless radical." A detailed study of Spence's stamps and a discussion of other stamps that could be his, as well as extensive quotations from his writings on which the plots of tokens were based, are reflected in the article RH Thompson, "The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814)", British Numismatic Journal Vol. 38 (London: BNS 1969), pp. 126-162, and The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814): Additions and Corrections, ibid. Vol. 40 (1971), pp. 136-138. the uses evolving of money. The Howard Linecar Memorial Lecture 2003" in British Numismatic Magazine Vol. 73 (London: BNS 2003), pp. 69-83, and David Dykes, "Some Reflections on Provincial Coinage, 1787-1797", ibid. pp. 160-74. Nothing significant is said about Spence, but Dykes calls him a "reckless radical." A detailed study of Spence's stamps and a discussion of other stamps that could be his, as well as extensive quotations from his writings on which the plots of tokens were based, are reflected in the article RH Thompson, "The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814)", British Numismatic Journal Vol. 38 (London: BNS 1969), pp. 126-162, and The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814): Additions and Corrections, ibid. Vol. 40 (1971), pp. 136-138. the uses evolving of money. The Howard Linecar Memorial Lecture 2003" in British Numismatic Magazine Vol. 73 (London: BNS 2003), pp. 69-83, and David Dykes, "Some Reflections on Provincial Coinage, 1787-1797", ibid. pp. 160-74. Nothing significant is said about Spence, but Dykes calls him a "reckless radical." A detailed study of Spence's stamps and a discussion of other stamps that could be his, as well as extensive quotations from his writings on which the plots of tokens were based, are reflected in the article RH Thompson, "The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814)", British Numismatic Journal Vol. 38 (London: BNS 1969), pp. 126-162, and The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814): Additions and Corrections, ibid. Vol. 40 (1971), pp. 136-138. 73 (London: BNS 2003), pp. 69-83, and David Dykes, "Some Reflections on Provincial Coinage, 1787-1797", ibid. pp. 160-74. Nothing significant is said about Spence, but Dykes calls him a "reckless radical." A detailed study of Spence's stamps and a discussion of other stamps that could be his, as well as extensive quotations from his writings on which the plots of tokens were based, are reflected in the article RH Thompson, "The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814)", British Numismatic Journal Vol. 38 (London: BNS 1969), pp. 126-162, and The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814): Additions and Corrections, ibid. Vol. 40 (1971), pp. 136-138. 73 (London: BNS 2003), pp. 69-83, and David Dykes, "Some Reflections on Provincial Coinage, 1787-1797", ibid. pp. 160-74. Nothing significant is said about Spence, but Dykes calls him a "reckless radical." A detailed study of Spence's stamps and a discussion of other stamps that could be his, as well as extensive quotations from his writings on which the plots of tokens were based, are reflected in the article RH Thompson, "The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814)", British Numismatic Journal Vol. 38 (London: BNS 1969), pp. 126-162, and The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814): Additions and Corrections, ibid. Vol. 40 (1971), pp. 136-138. A detailed study of Spence's stamps and a discussion of other stamps that could be his, as well as extensive quotations from his writings on which the plots of tokens were based, are reflected in the article RH Thompson, "The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814)", British Numismatic Journal Vol. 38 (London: BNS 1969), pp. 126-162, and The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814): Additions and Corrections, ibid. Vol. 40 (1971), pp. 136-138. A detailed study of Spence's stamps and a discussion of other stamps that could be his, as well as extensive quotations from his writings on which the plots of tokens were based, are reflected in the article RH Thompson, "The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814)", British Numismatic Journal Vol. 38 (London: BNS 1969), pp. 126-162, and The Dies of Thomas Spence (1750-1814): Additions and Corrections, ibid. Vol. 40 (1971), pp. 136-138.

A good introduction to the politics and society of 18th century England can be found in Roy Porter, English Society in the Eighteenth Century (London: Penguin 2nd edn. 2001). Revelations of left-wing political parties on revolutionary patriotism can be found in Hugh Cunningham, "The Language of Patriotism, 1750-1914" in History Workshop Journal Vol. 12 (Oxford: OUP 1981), pp. 8-33.

Spence's most important work is The Real Rights of Man, published in Pig's Meat No. 3 (London: 'The Hive of Liberty' 1795), pp. 220-229, was reprinted in M. Beer (ed.), The Pioneers of Land Reform: Thomas Spence, William Ogilvie, Thomas Paine (New York: Alfred A. Knopf 1920), and also in H. T. Dickinson (ed.), The Political Works of Thomas Spence (Newcastle: Avero 1982); most of these books and articles can be found in online libraries.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge