Online collections

monedastodas.com

All collections » Tokens » Thomas Mind

In this article, I would like to return to the topic of eighteenth-century provincial token minting, which I touched upon earlier in my study of the work of John Gregory Hancock and the Westwood Brothers and their mutual interest in token production (John Gregory Hancock and the Westwood Brothers: An Eighteenth-Century Token Consortium). , BNJ, 69 (2000), 173-86). This time I would like to talk about another token producer from Birmingham. Like Gallius Caesar, my story will be in three parts: some comments about manufacturers in general, a basic story about Thomas Mind, and finally an exploration of his tokens. Also, you will be able to make sure that this topic raises more questions than answers.

Eighteenth century tokens, as an acceptable substitute for the missing official small denomination coins, owe their appearance to Thomas Williams, a copper magnate and initiator of the famous Druid pennies and halfpennies of the Parys Mines Company of Anglesey. But his refusal to make these tokens in 1789, and the halfpenny he had been producing for a little over two years on behalf of John Wilkinson for his chief rival Matthew Bolton, left the production of tokens in the hands of Bolton and his own protégé, John Westwood, who dominated the business. over the next three years (for Thomas Williams' transfer of token production to Matthew Bolton, see David Vice, The Soho Mint & the Anglesey Tokens of the Parys Mine Company, Format, 33, 2-9; and for Bolton's token production, see Richard doty, The Soho Mint & the Industrialization of Money (London, 1998), especially pp. 297-3). The original circulation of tokens within the industrial community gained wider acceptance after they became familiar to the public and quickly spread from masters of heavy industry to commercial enterprises in bustling seaports and industrial cities at the forefront of the economic revolution. Until about 1792, a large number of so-called provincial coinage tokens were made for just such clients. However, in recent years there has been a radical change in the very essence of tokens and their producers. how they became familiar to the public and quickly spread from masters of heavy industry to commercial enterprises in the bustling seaports and industrial cities at the forefront of the economic revolution. Until about 1792, a large number of so-called provincial coinage tokens were made for just such clients. However, in recent years there has been a radical change in the very essence of tokens and their producers. how they became familiar to the public and quickly spread from masters of heavy industry to commercial enterprises in the bustling seaports and industrial cities at the forefront of the economic revolution. Until about 1792, a large number of so-called provincial coinage tokens were made for just such clients. However, in recent years there has been a radical change in the very essence of tokens and their producers.

When large orders from industrial and commercial enterprises began to decline sharply, new token production customers began to appear, concentrated primarily in small country towns south of the watershed between the Severn and Trent basins. By this time, the regions that experienced a shortage of small change in the past were quite well provided with tokens, and finding new customers was very difficult. In November 1792, John Wilkinson complained that "so many private manufacturers are engaged in minting many tokens themselves, so that now I cannot earn a quarter of what was possible a year ago." (Quoted from a letter dated 26 November 1792 to Matthew Bolton, published in W.H. Chaloner, “New Light on John Wilkinson's Token Coinage”, Seaby's Coin and Medal Bulletin, No. 362,

The leaders among the new manufacturers were William Latwich (William Lutwyche 1754-1801) and Peter Kempson (Peter Kempson 1755-1824), who had access to local shopkeepers and large merchants, mainly in the southeast of the country, where they found customers who had a need in the manufacture of tokens in small circulations. Tokens, which initially served as a bargaining chip, themselves became a commodity. Traveling salesmen were sent from Birmingham to look for new customers and deliver finished products. Thus, for example, William Latvich provided customers in Kent and Sussex during 1794, covering at least eighteen towns and villages. The tokens he made make it possible to trace the route of his agents from Canterbury to Sandwich or Deal Town along the coast of Hastings and back to Maidstonenoon through the Weld.

It is in this context that we must view the activities of the Birmingham token makers listed in the table of engravers and makers that Charles Pye included in the fourth edition of his book (Charles Pye, Provincial Coins and Tokens, issued from the Year 1787 to the Year 1801 (Birmingham, 1801), [p.2]). In it he lists seventeen producers: Matthew Bolton, Thomas Dobbs, John Gimblett, James Good, John Gregory Hancock, Bonham Hammond, John Stubbs Jorden, Joseph Kendrick, Peter Kempson, William Lutwich, William Mainwaring, Joseph Merry, Thomas Mind, James Pitt , Samuel Waring, John Westwood Sr., John Westwood Jr. Ironically, he omits the three makers mentioned in his detailed Index of Provincial Coins: R. B. Morgan, William Simmons, and Ovadius Westwood.

For the reasons I mentioned last time, I think we should strike the artist and engraver John Gregory Hancock off this list, unless he was a "partner" of the Westwoods. Perhaps we should also remove William Mainwaring, who was a hardware artisan, although he had previously worked as a medalist for Lutwich for a long time. On the other hand, perhaps we should add the machine maker William Whitmore, who, according to Miss Banks, was responsible for some issues of halfpenny for the Birmingham Mining and Copper Company (Sarah Sophia Bank, Ms Catalog of Coin Collection, VI - Tokens, p. 186: BM, Department of Coins and Medals, Arc R 19). Based on the above, one should not unconditionally trust Chiles Pye. This means that the information about the production of tokens is actually more confusing than we previously thought.

Of all the producers listed by Charles Pye, only Latvich described himself in the catalogs of his contemporaries as a producer of "provincial coins", and also was engaged in the manufacture of halfpenny and farthings specifically to advertise his production. Two copper magnates Dobbs and John Westwood (the latter, like Bolton, was a major industrialist), two hardware artisans (Mainwarning and Merry), two toy makers (Mind and Simmons), a locksmith (Pitt), and seven button makers (Gimblett, Good, Hammond , Kendrick, Kempson, Morgan and Waring). They all had access to hand presses and presses, which even by the 1750s were already quite sophisticated - Whitmore and Company made them in addition to supplying large machines for Thomas Williams in the early years of token minting - so even if the minting for the main companies was only provincial , each had the necessary equipment to do so (Eric Hopkins, The Rise of the Manufacturing Town: Birmingham and the Industrial Revolution (Stroud, 1998), pp.). For the same reason, Birmingham had a reputation as a city of counterfeiters (Brummagem - made in Birmingham).

It follows from Charles Pye's research that apart from Kempson and Lutwich - along with Bolton and Westwood, who I have excluded here - the individual issuances of the above producers were very limited (it must be emphasized that I only counted genuine provincial coins and private issue tokens that were in circulation as a small coin, as well as a medal for collectors). Counting the releases of Kempson and Latvich tokens, we get 72 and 75 different releases, respectively. For the rest, the number is as follows: Dobbs - 2, Gimblett - 1, Hammond - 1, Good - 12, Jorden - 4, Kendrick - 4, Mainwaring - 4, Morgan - 1, Mind - 6, Pitt - 4, Merry - 1, Sammons - 1, Waring - 3 and Whitmore - 1. In addition, with the exception of Mainwaring and Whitmore, most producers appear on the scene rather late: Dobbs in 1794-95, Hammond not earlier than 1797, Good in 1795-97, Jorden in 1795-96, Kendrick in 1796-97, Pitt in 1796-97, Merry in 1795 and Waring in 1793 and 1795. John Gimblett is apparently responsible for issuing the half-crown tokens for the Birmingham workhouse at the beginning of 1788, and Mind a year later was engaged in the production of shillings for the Basingstoke canal. The Gimblett half-crown is his only recorded issue, while the Mind shillings stand out from the rest of his tokens because they were issued from 1794 to 1797. These tokens also stand out from the rest with their high denomination. The Birmingham workhouse tokens, sui generis, were probably not meant to be circulated; known specimens issued in silver, white metal, bronze and copper. John Gimblett appears to be responsible for issuing half-crown tokens for the Birmingham workhouse in early 1788, and Mind a year later was involved in the production of shillings for the Basingstoke canal. The Gimblett half-crown is his only recorded issue, while the Mind shillings stand out from the rest of his tokens because they were issued from 1794 to 1797. These tokens also stand out from the rest with their high denomination. The Birmingham workhouse tokens, sui generis, were probably not meant to be circulated; known specimens issued in silver, white metal, bronze and copper. John Gimblett appears to be responsible for issuing half-crown tokens for the Birmingham workhouse in early 1788, and Mind a year later was involved in the production of shillings for the Basingstoke canal. The Gimblett half-crown is his only recorded issue, while the Mind shillings stand out from the rest of his tokens because they were issued from 1794 to 1797. These tokens also stand out from the rest with their high denomination. The Birmingham workhouse tokens, sui generis, were probably not meant to be circulated; known specimens issued in silver, white metal, bronze and copper. The Gimblett half-crown is his only recorded issue, while the Mind shillings stand out from the rest of his tokens because they were issued from 1794 to 1797. These tokens also stand out from the rest with their high denomination. The Birmingham workhouse tokens, sui generis, were probably not meant to be circulated; known specimens issued in silver, white metal, bronze and copper. The Gimblett half-crown is his only recorded issue, while the Mind shillings stand out from the rest of his tokens because they were issued from 1794 to 1797. These tokens also stand out from the rest with their high denomination. The Birmingham workhouse tokens, sui generis, were probably not meant to be circulated; known specimens issued in silver, white metal, bronze and copper.

I'm afraid few people will be able to add something to what Charles Pye said. Even Bolton, despite his extensive archive, appears to us as a very mysterious person, not to mention others who lived one or two generations before the advent of bureaucratic accounting and left very little information about themselves in history.

Thomas Mind is a kind of inhabitant of the “land of the missing” (a phrase from “The Forest and the Fort” by the American historical novelist Harvey Allen (1889-1949): “The past is the land of the missing and anyone who is not immortalized can be found there, combining perseverance and luck). A prominent representative of a group of humble masters for the most part - we actually know little more about him than can be summarized in one paragraph (the biographical data given in this and the next paragraph are based on materials from the archives of Herefordshire and Birmingham; see also Eric Delieb, The Great Silver Manufactory: Matthew Boulton and the Birmingham Silversmiths 1760-1790 (London, 1971), wherever information about the Mind family was available). It is known that he was born in 1741 in the small town of Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, in the family of local attorney William Mind, hereditary yeoman, with lands bordering the county of Monmuntshire. The elder Mind had a small fortune and after his death in 1769 he left four sons: the elder William inherited his father's business; John, became the owner of an ironworks in Ross-on-Wye and had interests in the Forest of Dean; Philip, referred to as "the gentleman," farmed the family's estates outside of Ross-on-Wye; the youngest son, Thomas, received £500 and expected a share of the profits from the Birmingham ironworks. Due to a small inheritance, Thomas began to engage in trade. He was not listed in Birmingham directories until 1787, when he acted as a toymaker at the junction of Whittall Street and Steelhouse Lane, until his death in 1799. It can be assumed

In his will, he left less than £300 to his wife Sarah and daughter. Saka Cox, being a widow, became Mind's second wife, whom he married only in 1797. Despite the gaps in Mind's biography, we know that in January 1762 he married Catherine Bolton, Matthew Bolton's sister, who had at least five children between 1763 and 1771. In January 1762, Mind, barely twenty-one, had completed his apprenticeship, which gave him the right to trade and marry. It is also unknown what happened to Catherine Bolton, but the Mind-Bolton family bond was strong; the eldest daughter Anne Mind assisted her daughter Anne Bolton, who was an invalid and from 1787 worked as a housekeeper at Soho House until she married in 1794. "Miss Mind" is often mentioned in Bolton's notes. Apparently Ann Mind was not well liked; she was stubborn and headstrong, behaved like a hostess at Soho House and treated her cousin inappropriately. Charlotte Matthews commented that Ann wanted no more harm than getting married so that she could finally leave home (I am indebted to Val Loggy, curator of Soho House; Fiona Tait of the Birmingham Archives for providing information on Ann Mind; Charlotte Matthews, who shared the opinion of Mrs. Watt Bolton appears to have been quite generous to the Mind family and their poor father, whom he backed with a fairly large loan on at least one occasion.) Fiona Taite of the Birmingham Archives for providing information on Ann Mind; Charlotte Matthews, who shared the opinion of Mrs. Watt. Apparently Bolton was quite generous to the Mind family and their poor father, whom he backed up with a fairly large loan on at least one occasion.) Fiona Taite of the Birmingham Archives for providing information on Ann Mind; Charlotte Matthews, who shared the opinion of Mrs. Watt. Apparently Bolton was quite generous to the Mind family and their poor father, whom he backed up with a fairly large loan on at least one occasion.)

In fact, that's about all we can say about Thomas Mind at the moment; a blurry image of the youngest son, who comes from a poor provincial family, who went into commerce in a booming industrial city, married to become a successful industrial family, and ultimately never lived up to his potential and often exuded an air of helplessness. What can be said about the tokens of this unfulfilled toy master. Obviously, they were a side activity to his main job, to say the least, as he produced only six issues in all time. Despite their mediocre manufacture, the tokens appealed to James Wright of Dundee when he first saw them, as they well illustrated the power and significance of England's progress at the end of the eighteenth century, penetrated the minds of the people and underpinned commercial development, the growth of communications, the improvement of the quality of life and the improvement of the navy (James Wright, signing as "Civis", published descriptions of tokens in The Monthly Magazine and British Register (December 1796), pp 868-9 This article was an amalgamation of two articles previously published in The Edinburgh Magazine (February 1796), pp. 131-4 and (May 1796), pp. 325-6). But each of the six issues is a separate work, with a different story and a lot of problems. This article was an amalgamation of two articles previously published in The Edinburgh Magazine (February 1796), pp. 131-4 and (May 1796), pp. 325-6). But each of the six issues is a separate work, with a different story and a lot of problems. This article was an amalgamation of two articles previously published in The Edinburgh Magazine (February 1796), pp. 131-4 and (May 1796), pp. 325-6). But each of the six issues is a separate work, with a different story and a lot of problems.

Mind's first issue captures the feeling of industrial development very accurately, as it was produced in one of the early factories that did much to boost Britain's economic growth at the end of the eighteenth century. It's a shilling of the Basingstoke Canal.

The 37½-mile Basingstoke Canal was built

at the peak of the canal mania that swept the country in the early 1790s to

navigate from the town of Basingstoke to the River Thames, across the River Way

near Byfleet (for more on the Basingstoke Canal, see PAL Vine, London's Lost

Route to Basingstoke (Stroud, 1994), pp. 16-40, and Edward W. Paget-Tomlinson,

The Complete Book of Canal & River Navigations (Wolverhampton, 1978), pp. 93). The

canal allowed northern Hampshire to export timber, malt and grain to London, and

bring back coal, groceries and household items. The construction of

the canal continued from 1788 to 1794, completed two years later than planned

due to mismanagement and constant debt. People were told that

the canal “was of great importance to Basingstoke and the neighboring lands”

([Richard Thomas Samuel]. The Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart (22 June 1881), 639.

This rumor is also given in R. C. Bell, Commercial Coins 1787-1804 (Newcastle

upon Tyne, 1963, p. 46). This enterprise, bankrupt from the start,

subsequently proved unable to carry more goods than the existing overland routes

allowed, and as a result brought in much less profit than previously expected; the

reason for this lay in the inability to compete with the rapidly developing road

system, both in terms of cost and speed. Ironically, a few years

later, materials for the construction of railway networks in London and

Southampton were transported along the canal,

The token has a diameter of 30 mm and an

average weight of 13.8 g, which is slightly larger than the standard provincial

halfpenny. The front side shows a sailing barge carrying a large

wooden log and some other goods; the reverse side depicts a shovel

with a pickaxe in a wheelbarrow; a suitable token design for the

trade channels that supply London with the timber needed for the navy, which is

directly dependent on a few simple tools and the hard work of a myriad of

diggers. On the stamp of the front side there is a re-engraving

from the number "8" to "7" in the date, which is typical for all copies that I

have seen. Ribbed edge, described by Bell as a repeating feather

(overlapping feather engrailed),

According to James Wright, this token was

in fact a medal minted by order of the Pinkerton Canal Manager, to be given to

each warehouse owner nearby as an advertisement. On the other hand,

Charles Pai suggested that the tokens were paid as wages and circulated among

the workers involved in the construction of the canal. Thomas Sharp

agreed with Pye. Hamer, following Samuel, allowed the existence of

both options: "As a manager, John Pinkerton, at an early stage of construction,

undoubtedly wanted to impress entrepreneurs and everyone who later could use the

transportation services provided, as well as issue a new local currency into

circulation" . There is no reliable information about the existence

of silver variants of the Pinkerton shilling, which are almost certainly

apocryphal (GM 1797, Part I (January), 33; Charles

Pye, Provincial Coins and Tokens, issued from the Year 1787 to the Year 1801

(Birmingham, 1801), p. 6; Thomas Sharp. A

Catalog of Provincial Copper Coins … in the collection of Sir George Chetwynd

(London. 1834), p. 2; [Richard Thomas Samuel]. The

Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart (June 22, 1881); [Hamer] in D&H, Vol. I,

p. 39; PAL Vine, London's Lost Route to Basingstoke

(Stroud, 1994), p. 31). At first glance, Hamer's

conclusion seems reasonable. A well-known history of canal

construction claims that the tokens were issued to pay part of the labor of

diggers and were redeemable at George's Inn in Odyham, where the main center of

construction was located. The same source reports that they could

be given as something special, thus hinting at variants in silver, the

likelihood of which is very negligible,

Pinketron tokens are quite rare and even

in Wright's time (1796) each was worth a few shillings. Wright

assigned them the second degree of rarity - RR, Pye classified as R. The copies

that have come down to us have practically no traces of circulation, and,

apparently, were minted with one pair of stamps. Obviously, the

tokens were issued in a small circulation. If they were intended

for circulation as a currency, then because of their overvalued value, compared

with other more significant tokens of a smaller denomination, such as the Druid

pennies, they met with dissatisfaction and their release was discontinued. Therefore,

most likely, Pinkerton's shillings were not intended to pay wages and Wright's

information about the issue for the presentation was much closer to reality. More

on this below.

Regardless of their purpose, Pinkerton

shillings were not issued by the Basingstoke Canal. Just as John

Pinkerton was not a company manager. The practice of most canal

builders was to appoint a local attorney as the manager, acting as head of the

board of directors. It was also during the construction of the

Basingstoke Canal where the local attorney, Charles Best (1748-1816), also

acting town clerk, served as steward on an interim basis for almost forty years. Then

who was John Pinkerton? The construction of the canals was carried

out by contractors who worked under the supervision of a chief engineer

responsible for the design of the canal, hiring labor and remuneration. It

was the same case. The chief engineer was William Jessop

(1745-1814), perhaps the greatest canal-builder of his day, while

Yorkshireman John Pinkerton, with one of several brothers, were prime

contractors and were among the best. In fact, the Pinkertons were

the largest and most famous canal building firm and the only ones to carry out

nationwide contracts. John Pinkerton was an early member of the

Smeatonian Society, which also included the engineer William Jessop, with whom

they worked together on various projects from the 1770s. In this

way, Pinkerton was engaged in the construction of the canal, as well as the

organization and payment of labor (Edward W. Paget-Tomlinson, The Complete Book

of Canal & River Navigations (Wolverhampton, 1978), pp. 346-7 and Charles

Hadfield and A. W. Skempton, William Jessop , Engineer (Newton Abbot, 1979),

pp. 19-20).

The Pinkerton tokens are dated 1789 and

for a long time I could not figure out if this was a memorable or actual date of

issue. The construction of the canal began in the autumn of 1788,

which is consistent with the period when Pinkerton paid wages to his diggers and

carried out an advertising campaign among future clients. Pinkerton

had come to Basingstoke from Birmingham, where he had worked on the construction

of the Birmingham and Fazeli Canal and was well aware of the token issues. In

this case, it is strange why Mind was turned to for the production of tokens. Why

not John Westwood or Matthew Bolton? At that time they were the

main producers of tokens. Perhaps he really approached Bolton, who

was too busy with other projects and sent him to his brother-in-law, whom

he took into his business two or three years ago and took care of his need for

commissions. The more logical hypothesis for me, however, is that

despite the date, the tokens were actually made in the mid-1790s, when Mind is

known to have been manufacturing them. In the summer of 1794,

Pinkerton completed the construction of the Basingstoke Canal, and at the moment

it would be appropriate to present to the owners of the canal a memorable gift,

reminiscent of his building skills over the past five years. But at

the moment, in the absence of concrete evidence, this can only be conjecture; a

date closer to 1794 would have been more likely if, as Pye claims, the engraver

was Thomas Wyon. that despite the date, the tokens were actually

made in the mid-1790s, when Mind is known to have been producing them. In

the summer of 1794, Pinkerton completed the construction of the Basingstoke

Canal, and at the moment it would be appropriate to present to the owners of the

canal a memorable gift, reminiscent of his building skills over the past five

years. But at the moment, in the absence of concrete evidence, this

can only be conjecture; a date closer to 1794 would have been more

likely if, as Pye claims, the engraver was Thomas Wyon. that

despite the date, the tokens were actually made in the mid-1790s, when Mind is

known to have been producing them. In the summer of 1794, Pinkerton

completed the construction of the Basingstoke Canal, and at the moment it would

be appropriate to present to the owners of the canal a memorable gift,

reminiscent of his building skills over the past five years. But at

the moment, in the absence of concrete evidence, this can only be conjecture; a

date closer to 1794 would have been more likely if, as Pye claims, the engraver

was Thomas Wyon. In the summer of 1794, Pinkerton completed the

construction of the Basingstoke Canal, and at the moment it would be appropriate

to present to the owners of the canal a memorable gift, reminiscent of his

building skills over the past five years. But at the moment, in the

absence of concrete evidence, this can only be conjecture; a date

closer to 1794 would have been more likely if, as Pye claims, the engraver was

Thomas Wyon. In the summer of 1794, Pinkerton completed the

construction of the Basingstoke Canal, and at the moment it would be appropriate

to present to the owners of the canal a memorable gift, reminiscent of his

building skills over the past five years. But at the moment, in the

absence of concrete evidence, this can only be conjecture; a date

closer to 1794 would have been more likely if, as Pye claims, the engraver was

Thomas Wyon.

I would like to note an interesting fact:

during earthworks on the territory of Basing House, a local watchmaker will find

a cache with 800 guineas, which were supposedly hidden during the siege by

Cromwell. Although I have not been able to find contemporary

confirmation of this find (a supposed find is mentioned in Vine, London's Lost

Route to Basingstoke (Stroud, 1994), p. 30, and Arthur Freeling. Guide to the

London & Southampton Railway (London. 1839), p. 7).

The next issue of Mind tokens is dated

1794 and takes us away from industrial themes to shopkeepers' tokens. This

halfpenny was commissioned by John Fowler and payable in London.

The question is who Fowler was. Samuel speculates that John Fowler traded oil and tinplate at 78 Long Acre, but this fact is not without doubt. I have not been able to identify the source of Samuel's information, but the iconography of the token is consistent with his suggestion (Richard Thomas Samuel, The Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart (22 June 1882), 685). The token has the usual halfpenny diameter of 28 mm and weight of 9 g. Neptune is depicted on the front side - Samuel believes that the facial expression does not look majestic enough for the god of the seas (his hair and beard are of very modest length) and more resembles an ordinary sea wolf, and on the back On the side is a whaler hunting scene. It must be stressed that whale oil was a very important commodity in the late eighteenth century, especially in the new growing urban communities. Lighting of streets, houses, factories and shops became more and more dependent on it. As early as the 1740s, London had over five thousand street lamps burning on whale oil. Whale oil was also used in the manufacture of soaps, lacquers and paints, rigging, and in the process of dressing coarse woolen cloth such as military twill, which was in great demand at this time. And, of course, in the new age of machines there was a rapidly growing demand for whale oil, which was used as a lubricant (W. Scoresby, An Account of the Arctic Regions, with a History and Description of the Northern Whale Fishery (Edinburgh. 1820), Vol. II, pp. 420-1, and Gordon Jackson, The British Whaling Trade (London, 1978), pp. 55). , but mainly lamp oil and candles, although it is possible that he may also have been a supplier of oil for street lighting. Fowler's shop also stocked spermaceti candles, which outperformed old-fashioned tallow candles in their lack of smoke and their bright, long-lasting burn. It is very possible that he was one of those merchants who, a few years later, prevented the introduction of gas street lighting in London. And that brings us back to the token. Neptune may have been depicted to give the taste of the sea. But its proximity to the whaling scene, if deliberate, may indicate a source of whale oil in the Southern Ocean, which was of great importance to Britain after the American Revolution (1775-1783) and the colonization of Australia, in part because of the existence of sperm whales there, necessary for the extraction of spermaceti, but also because of the large concentrations of northern right whales (Eubalaena glacialis), which in the 1790s accounted for between one-third and one-half of all imports of whale oil (for developments in the South Sea, see Gordon Jackson, The British Whaling Trade (London , 1978), pp. 91-116 and Vincent T. Harlow, The Founding of the Second British Empire, (London, 1964), Vol. II, pp. 293-328). The token depicts a sleek whale firing two jets, as Michael Mitchiner said, which is a highly stylized “artistic element” (Michael Mitchiner, Jetons, Medalets and Tokens, Vol. Ill (London, 1998), p. 20) – but rather the engraver wanted to show a powerful V-shaped jet, which is a sign of a smooth whale (Nigel Bonner, Whales of the World (London, 1989), p.51). Undoubtedly, given the rather limited space, the scene is reproduced quite accurately, despite a false sense of calm in this rather dangerous trade. A few seconds later, the scene could be completely different, because the wounded whale could try to get rid of his pursuers.

Spermaceti brings us to the next token, more precisely to a series of three tokens; John Palmer's father, who sold candles and spermaceti in Bath, also had interests in the theater and a brewery. Thomas de Quincey spoke of John Palmer (1742-1818) as follows: “he achieved two difficult things on our planet, ... invented the postal wagon and married the daughter of a duke” (Thomas de Quincey, English postman (London [Everyman Edition], 1912 p. 1. An example of marital misidentification: Lady Madeleine Gordon actually married Charles Fish Palmer, who had nothing to do with John Palmer.)

John

Palmer, 1793. Pencil Drawing by

John

Palmer, 1793. Pencil Drawing byWe will not be distracted by the second achievement, which has no basis, and let's talk about the first. Tokens are dedicated to the invention of postal carts and the reform of postal delivery. Three different types were produced, two undated and a slightly reduced size third dated 1797.

Middlesex

D&H halfpenny mail carts: 363, 366 and 364

Middlesex

D&H halfpenny mail carts: 363, 366 and 364

Undated halfpennies have a standard

diameter of 28 mm and an average weight of 8.75 g, dated ones have a diameter of

27 mm and a weight of 7.5 g. On the front side of the tokens, a horse-drawn mail

cart is depicted moving at high speed with slight variations in the text legend; on

the dated version, the legend is copied from the token with the initials “JF”. The

dynamic scene is not very skillfully engraved (according to Pye, Wion was the

engraver of the tokens), this is especially true of the inscriptions on the

token with the initials “AFH”.

Pai will not help us with dates or

producers of undated tokens. As for the dated ones, we can get some

information from modern catalogs. John Hammond's first catalog,

edited by "Christopher Williams" - and in fact by Hammond himself - which was

published in early 1795, contains information only about the token with the

initials "JF". Spence's catalog, published in mid-May 1795,

contains a description of two halfpennies with the initials "JF" and "AFH",

which subsequently appeared in the second edition of Hammond, published in

August 1795 - while both authors noted that the tokens with the initials " AFH"

- "new". For more precise information, we learn from Miss Banks,

who acquired her copies: “JF” in January 1795 and “AFH” in May 1975. Thus,

we can determine the minting time of all three tokens: 1794/95 - “JF”,

What Ms. Banks did not do, or any catalog

of the time, was not to decipher the initials "JF" and "AFH". Hamer

attributes the initials "AFH" to the London merchant Anthony Francis Haldimand,

while other authors attribute the initials "JF" to their contemporary engraver

James Fittler. At first glance, none of them have an obvious

connection with Palmer, so Waters dismissed these assumptions as untenable

(Hamer in D&H, Vol. I, Middlesex 'Introduction to the Halfpenny Section'; RC

Bell, Commercial Coins 1787-1804 (Newcastle upon Tyne, 1963), p. 113; Arthur W.

Waters, Notes on Eighteenth Century Tokens (London, 1954), p. 14). There

is a slight possibility that the tokens were produced by order of Fittler,

To John Palmer Esq' Surveyor and

Comptroller General of the Post Office:

This Plate of the MAIL COACH is

respectfully Inscribed

By his obedient humble Servant, James

Fittler.

Postal

cart. Engraving by James Fittler after a painting by George

Robertson

Postal

cart. Engraving by James Fittler after a painting by George

RobertsonGeorge Robertson died

in 1788 and we do not know when this engraving was made. The

published version was produced by Islington, commissioned by the merchant Robert

Pollard, no earlier than 1803. However, the fact that Palmer is

referred to as "Inspector and Comptroller General of the Post Office" implies

that the engraving was originally done no later than 1793, when he was removed

from office. It is quite reasonable to assume that the engraving is

dedicated to Palmer, as mentioned earlier, and despite the lack of other

evidence, one should not forget the coincidence of the initials on the token

with James Fittler (1758-1835), who carved engravings on the nautical theme for

the king, although the image of the mail wagon on the token has a slight

resemblance to the one depicted in Fittler's engraving and is much more

reminiscent of vignettes,

The less obvious version of the

production of tokens by Haldimand cannot be completely ruled out. Anthony

(Antoine) Francis Haldimand (1741-1817) was a significant figure in the city (a

biography of Haldimand is given in [Auguste Prevost], History of Morris, Prevost

& Co. ([London], 1904), pp. 1-6; and in The Dictionary of National Biography in

the entries 'Sir Frederick Haldimand' (his uncle) and 'William Haldimand' (his

son).

Anthony

Francis Haldimand (1741-1817), painted by John Francis Rigaud, RA (1742-1810)

Anthony

Francis Haldimand (1741-1817), painted by John Francis Rigaud, RA (1742-1810)

Of Swiss origin and born in Turin, he

settled in London as an importer of Italian silks, but was soon involved in a

number of other large-scale commercial ventures, including international credit

and banking, and financed the development of Belgrave Square. Certainly

he must have appreciated the new wagon mail service and may well have attended a

meeting of the city's merchants in a London tavern in 1792, organized by Palmer

to protest against the slow work of the post office. His name is

not among the participants in this meeting, but the assumption that the initials

"AFH" belong to him, although this is not impossible, is even more speculative

than the identification of "JF" with James Fittler.

But what was the purpose of issuing these

tokens? This is not the place to waste time on Palmer's postal

career (biography of Palmer in The Dictionary of National: Charles R. Clear.

John Palmer (of Bath), Mail Coach Pioneer (London, 1955), passim. (A valuable

study but suffering from a lack of references); Kenneth Ellis, The Post Office

in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1958), passim', Howard Robinson, Britain's

Post Office (London, 1953), pp. 103-9). Perhaps suffice it to say

that Palmer, appointed by Pitt to the post of Comptroller General in 1784 to

carry out reformist ideas for the transport of mail, with an

amateurish zeal and an arrogant nature, he is confronted with the entrenched

state of affairs in state institutions and ultimately jeopardizes his

relationship with the equally active and self-confident Postmaster General Lord

Walsingham, in whom he refuses to recognize his leader. It was a

difficult situation, and Palmer's intrigues to secure his office, which he

considered independent of the control of the Postmaster General, ultimately led

to his removal in 1792 and dismissal a year later. Palmer spent the

next twenty years trying to get restitution for losses incurred in the midst of

pamphlet confusion and the daily whirlwind of business. In such a

scenario, another reason for issuing the halfpennies with mail carts is likely; the

safety of the tokens suggests that they were indeed used as small coins and in

doing so acted as a means of protecting the name of Palmer before the public,

organized by Palmer's allies on his own initiative. The tokens had

no redemptive powers, and I disagree with Samuel's view that they were an

expression of gratitude on the part of wagon and inn owners who benefited from

Palmer's reforms. It is naive to think that they could issue such

tokens without indicating their name and location (Richard Thomas Samuel, The

Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart (23 August 1882, 202). Cf. the halfpence issued at

the George and Blue Boar (D&H: Middlesex 339 and 342) and the Swan with Two

Necks (W: 840, p. 129).

Consider the last token, which was also

issued by a merchant and, as befits someone who worked at the city’s naval

shipyard during the Revolutionary War with France, is made in patriotic and

nautical themes.

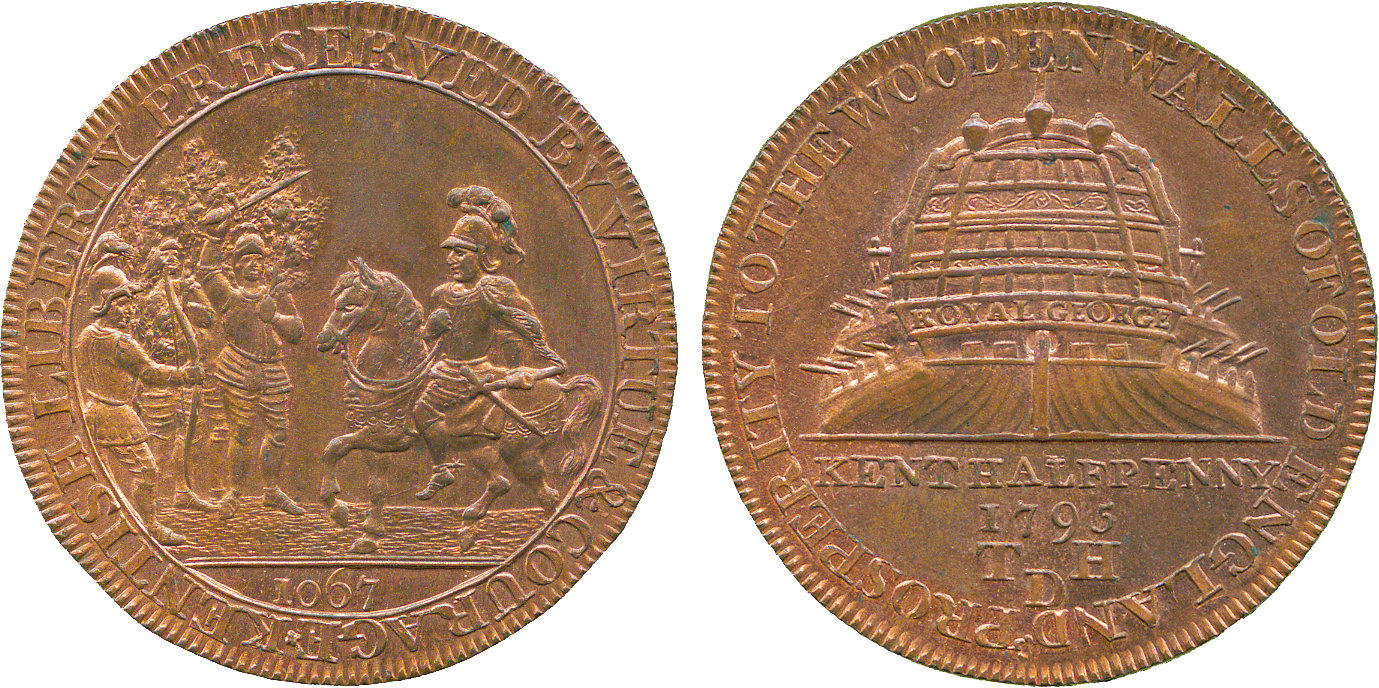

Thomas

Haycraft halfpenny, Deptford, Kent

Thomas

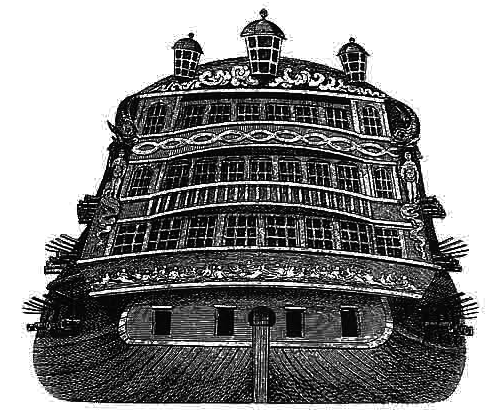

Haycraft halfpenny, Deptford, KentThe token (29 mm in diameter, average weight 9.45 g) was issued by Thomas Haycraft, a breakaway ironmonger in Deptford in 1796 (his son, also Thomas, was baptized at the independent church on Butt Lane in Deptford on May 4, 1778) . The obverse depicts a legendary scene from the history of Kent, no doubt intended to emphasize British contempt for enemy pretensions. The scene is a mythical confirmation of the Kentish rights of William I after the battle of Hastings (RC Bell, Commercial Coins 1787-1804 (Newcastle upon Tyne. 1963). p. 68). Until the thirteenth century, there was no central authority in this region, and although the Conqueror met Anglo-Saxon envoys who swore allegiance to him, signs of destruction were found at various places along his journey to London, showing little Kentish recognition (Edward Freeman, The Norman Conquest (Oxford, 1875), III, p. 538, n. 3). The reverse side is more obvious, but its design is unusual for two reasons. First, most of the ships depicted on the tokens are depicted sideways; there are exceptions, the most impressive of which is the Thames-Severn canal halfpenny (Gloucestershire D&H: 58-61). Here, however, this rule is broken in order to show with startling clarity the stern of a three-deck warship, the image of which is probably taken from an architectural drawing not unlike that shown in the engraving below, although the latter is taken from a later source on naval architecture. but its design is unusual for two reasons. First, most of the ships depicted on the tokens are depicted sideways; there are exceptions, the most impressive of which is the Thames-Severn canal halfpenny (Gloucestershire D&H: 58-61). Here, however, this rule is broken in order to show with startling clarity the stern of a three-deck warship, the image of which is probably taken from an architectural drawing not unlike that shown in the engraving below, although the latter is taken from a later source on naval architecture. but its design is unusual for two reasons. First, most of the ships depicted on the tokens are depicted sideways; there are exceptions, the most impressive of which is the Thames-Severn canal halfpenny (Gloucestershire D&H: 58-61). Here, however, this rule is broken in order to show with startling clarity the stern of a three-deck warship, the image of which is probably taken from an architectural drawing not unlike that shown in the engraving below, although the latter is taken from a later source on naval architecture.

The

stern of a British warship built in 1758.

The

stern of a British warship built in 1758.Knowing the real name of the ship depicted behind the token, the engraver (unidentified by Pye), working in a confined space, tried to convey the features of the stern of the magnificent naval vessel only in general terms, without the possibility of identifying it. The image of the stern led Samuel to the idea that this was the “Royal George”, which, capsized during repairs, sank at Spithead in 1782, killing Admiral Richard Kempenfelt and about 900 crew members. Here, however, we have the successor to Admiral Kempenfelt's ill-fated flagship: the fourth Royal George, pictured below, launched at Chatham in 1788 and mentioned in the news of 1795 as the flagship of Admiral Alexander Hood in the battle of the island of Groix, and a year earlier participating in Glorious First of June battle (both victories were the subject of many medals and tokens,

HMS

Royal George, 1788-1822. (From an aquatint of 1806,

HMS

Royal George, 1788-1822. (From an aquatint of 1806,Again, almost nothing is known about the issuer of the token. Deptford had one of the largest food depots and also had a naval port, and it could be that Haycraft was a naval contractor, but don't make that assumption the main reason for the release. Haycraft's tokens were produced in comparatively large quantities and are the only known issue of provincial coins in populous Deptford requiring large amounts of small change; at least three obverses and two reverses are known to be payable at Chatham, Dover and Deptford. The most likely reason for issuing a halfpenny with patriotic slogans addressed to the local population may be the desire of an ordinary merchant to take part in large projects. We managed to learn a lot about Mind tokens. Particularly the Pinkerton shillings, which, despite a mistake in the engraving, proclaim themselves, being at the same time a relatively inexpensive product of a small workshop. Their production is by no means outstanding, nor is the engraving of the stamps themselves; the images are quite figurative, but the execution leaves much to be desired. Pye tells us that - with the exception of the Haycraft halfpenny - the engraver of the Mind tokens was Thomas Wyon (1767-1830). The engraving style of the unsigned work suggests that it may also be Thomas himself or his brother Peter (1767-1822). Thomas Wyon, along with two younger brothers and father George, took care of the family business in the workshop until his father's death in 1796 (Thomas and Peter appear in the Birmingham catalogs only after the death of father George, and in the Pye catalog in 1797. Up to that point, the only Wyon mentioned in the catalogs was George.) At the end of the eighteenth century, Wyon's workshop was heavily loaded with orders and it is very possible that some of the stamps were the work of his students and assistants. Unlike Kempson, Mind could not always count on Wyon's best stamp cutters. But, once again, this is just speculation, highlighting the suspense and uncertainty that lie in wait for researchers in the “land of the missing” in the production of provincial coins and the need to check and recheck much of what has been written about the tokens themselves, especially recently. that some of the stamps were the work of his students and assistants. Unlike Kempson, Mind could not always count on Wyon's best stamp cutters. But, once again, this is just a guess, highlighting the suspense and uncertainty that lie in wait for researchers in the “land of the missing” in the production of provincial coins and the need to check and recheck much of what has been written about the tokens themselves, especially recently. that some of the stamps were the work of his students and assistants. Unlike Kempson, Mind could not always count on Wyon's best stamp cutters. But, once again, this is just a guess, highlighting the suspense and uncertainty that lie in wait for researchers in the “land of the missing” in the production of provincial coins and the need to check and recheck much of what has been written about the tokens themselves, especially recently.

David Wilmer Dykes, The tokens of Thomas Mynd, BNJ, 70 (2000), 90-102